| |

An Unplanned Life

-718582.jpeg) Last night I watched a captivating1958 film called Inn of the Sixth Happiness, based on the true story of a British maid named Gladys Aylward (played by Ingrid Bergman), who leads fifty children over the mountains to safety in China after the Japanese invaded in 1937. Colonel Lin Nan, a Chinese officer (played by Curt Jurgen), who is part European, falls in love with Gladys, the single-minded British missionary. He has to make a choice between what his heart is telling him and his sense of duty. When the old Mandarin asks Colonel Lin Nan why he chose in favor of duty, the Colonel resignedly says, "My life is planned." The Mandarin responds, "A life that is planned is a closed life, my friend. It can be endured perhaps. But it cannot be lived." It made me think of how often I limit myself by planning. At this time of year I often make New Year’s resolutions with a set of goals and intentions for the year—all with a view towards having an “ideal life” where everything was perfect. It’s hard to find anything wrong with this. Why wouldn’t anyone want to make their life more worthwhile? Like everyone else, I’ve been well acculturated by society to do better, be a good person, and be productive. But what I overlook is that by having my life planned I am creating a “closed life,” where there is very little room for life to happen, for life to surprise me, for life to open up my heart. If I really want to be honest with myself, I plan because I do not feel that I am OK just as I am. I plan so that I will feel safe in a world that is not safe. I plan in the hope of finding some future happiness once I have reached my goals. The problem is that all these plans are made by our egoic minds to avoid pain and find pleasure. The human ego is notoriously unreliable in making choices that will truly benefit our awakening to greater peace and happiness. But what if I was able to see the underlying perfection of life right here, right now? What if I could see that nothing needs to be changed or improved? When I’m content to greet life exactly as it is, with both the good and the bad, then I can truly relax and be at peace. At the beginning of 2009 I posted a blog that began with a quote by the Jesuit priest Anthony de Mello. This year I’ll end with the same quote and “plan” to understand it more fully in 2010. “You want to hope for something better than what you have right now, don’t you? Otherwise you wouldn’t be hoping. But then, you forget that you have it all right now anyway, and you don’t know it.”

Dirty Dishes

Doing--or not doing--the dishes is a cause for disagreement among many couples. Sometimes the underlying causes are not what we think they are. Last Friday, during a session with our therapists David and Tom (who co-facilitate together), Linda brings up her frustration at my leaving dirty plates on the kitchen counter and not putting them in the dishwasher.“I don’t believe this,” I say, rolling my eyes. “I don’t want to waste time talking about dirty dishes in a session! This is something couples do in their first year of marriage. Surely we’re beyond all this!” “Well, it bothers me,” Linda says vehemently, “I want to talk about it, especially since we can’t talk about it without getting angry. I know there’s something bigger going on.” “What a waste of time,” I say squirming in my seat. “Besides, I try so goddamn hard to keep the counters clean. I obsess about it. I’m like an OCD gone wild. I put everything away. I clean the counter with paper towels, I get up every last crumb . . . and you accuse me of messing up the place? Damn it, I’m trying to do everything I can to please you.” “I don’t see why you have such a big problem putting things in the dishwasher. Is it that difficult?” “First you asked me not to leave the dishes out to air dry, and now I dry them and put them away. What more can I do to make you happy?” “Put the dishes in the dishwasher.” I feel a wave of anger. “But I do put them in!” “No you don’t. You neurotically take dishes out and wash them by hand.” “That was just once . . . and I enjoyed doing it. What’s the problem with that? It’s as if a seething volcano of anger is filling the room—all coming from me. And I never show my anger! “What’s the anger about?” Tom asks. An image surfaces of my stepmother Nancy doing the dishes before we’d even finished dinner. “My stepmother was so uptight she would grab the dishes off the table before we had finished eating and take them into the kitchen. And that was always the moment we were all beginning to have some fun after a few glasses of wine. For once my dad was happy . . . and she couldn’t stand it.” “Uh-oh, I did a Nancy,” Linda cringes. “Peter hated his stepmother. He told his friend over the phone that he hated her and wanted to kill her—and she was listening on the other line.” Tom raises his eyebrows. “That’s interesting.” “Yeah, I really did—and I meant it. I really did want to kill her . . . but let’s move on. I want to get deeper on this.” “Oh, that wasn’t deep enough?” Tom asks. We all break up laughing. “She really was cold and mean,” Linda adds.” “I used to get furious at her for lying in bed all day reading and watching TV. I get angry at Linda for doing the same thing.” “Nancy was not your mother, though, was she?” David asks. “No, she was the ‘wicked stepmother.’ Suddenly a realization dawns. “But I had no reason to get angry at Nancy! This has nothing to do with her. It’s all about my mother. She must have been sick and in bed with cancer, and lying in bed all day. I was frightened and had no idea what to do.” “You were only eight or nine then, weren’t you?” “Yeah, I vaguely remember standing in front of our couch, while my mom tried to take care of my little brother Richard, who was just a baby. She said something like, ‘You’re a big boy now. You have to help me. I’m not well.’ I wanted to please her, so I made up my mind to do whatever I could to help her.” “Was she sick then?” asks Tom. Linda jumps in, “I’m sure she was . . . it was about three or four years before she died.” “I must have realized that if I wasn’t a good boy, and didn’t help her, then she would die.” “Yeah, I’m sure it felt like you’d literally die,” David says. “That’s true. I was my mom’s favorite. She must have been really sick then—but no one told me anything. I can vaguely remember her coming home from the hospital, but . . .” “He doesn’t remember anything about his mom,” Linda adds. “What happened is that I did become invisible,” I say, shaking my head. “I was totally ignored. When my mom died I was left to fend for myself. The only way I could get love was by helping . . . by being a good boy. I had to produce. It was life or death.” Tom and David nod their heads and just listen. I’m so grateful for their quiet wisdom. “It’s no wonder I can’t relax. No wonder I’m so driven. I can’t even slow down, even for a second, or I’ll be dead. There is this terror of emptiness.” “So you have to keep running as hard as you can . . .” “Oh my God,” I say, turning to Linda. “My getting upset with you reading and watching TV is not because of you! It brings up the trauma of seeing my mother sick in bed, and having no idea what was going on.” Linda reaches out to touch my hand. “This has been so hard for you,” she says. “First you had to live through this with your mom, then with Fran when she was sick, and now me.” “And this whole thing about the dishes has nothing to do with Linda,” I say, getting back to our original argument. “I’m terrified that if I don’t do everything perfectly, I will die! I HAD to please my mom. No, it’s more than that . . .” “Dying isn’t enough?” Tom asks with a wink. We all laugh, relieving the tension. “I must have known on some level she was getting sicker and sicker. I was petrified.” “And no one said anything, making it even harder,” David says. “So feeling that I’m somehow failing Linda brings all this up again, especially since Linda is sick and in pain so much of the time.” “I don’t want to be,” she says lovingly. “I know, I know . . .” “And when you criticize me for not doing the dishes right, I feel hurt . . . like I’ve disappointed the person I love most in the world.” “Oh sweetheart, I love you so. The last thing I want to do is hurt you. You’re my love.” David and Tom smile. “I’m so sorry if I got angry at you.” We look deeply into each other’s eyes. I feel a warm sensation spreading through my belly . . . a huge knot of energy has been released. Our dogs, Kamalani and Lukey (always present for our therapy), have been chewing on hooves. They look up at us. So, you’ve finally figured it out?

Hurry-Worry Never Works

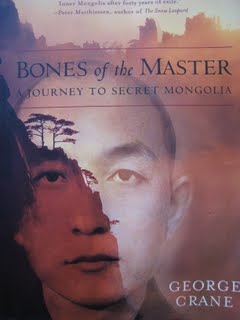

In 1959, Tsung Tsai, a Buddhist monk, escaped from the Red Army troops that destroyed his monastery, and walked three thousand miles across China to Hong Kong, nearly dying in the process. Years later he ends up living in upstate New York, where he builds his own house and lives a monastic life. During a snowstorm, he meets his neighbor, a young hippie poet from New York named George Crane. An unlikely friendship forms between them as they sip tea and read poetry together. Tsung Tsai shows the poet some poems in Chinese, and George gets very excited about the idea of translating them into English. But Tsung Tsai knows that it is not yet time. “Hurry-worry never works,” he says. George Crane later writes about this extraordinary friendship (and and their daring journey into Lower Mongolia) in his delightful book called Bones of the Master—A Journey to Secret Mongolia. I often think about Tsung Tsai saying, “Hurry-worry never works” in reference to my own life. Lately I’ve been obsessively driving myself to “get things done.” My busy little mind says, “If you can just finish this project, then you can relax.” Once I finish it, I’m saying, “You’ve got to get those letters out.” On and on it goes. Soon there is no time to breathe (because of my own self-imposed deadlines), and my body becomes tense and stressed out. It’s all about “me” having to get “my” projects done. What a vicious cycle. Today, while meditating, I could almost feel the frenzied rush of “hurry-worry” thoughts. I notice that it’s all about “my” thoughts, “my” feelings, and “my” worries. What would it be like not to have these thoughts? What would it be like not to be constantly thinking, “I need to do this, I need to do that?” I realize that I don’t have to live with these little gnats constantly buzzing around in my head. All I need to do is “flush” them out by dropping inside and being still. If I place my attention on what’s happening right here, right now, there's no room for the "me" thoughts. And when they come back (which they most certainly will), all I need do is take a few moments to be still once again. What’s left when they are gone? Nothing but empty awareness. When there’s no one there to claim these thoughts, there is nothing but peace. What a relief. The challenge is that if I do slow down, I have to look at why I’m so driven to get all this stuff done. I have to ask, “What is all this “doing” about? Do I need to create meaning in my life through doing, and more doing?” Is it all so that I will feel important, fulfilled, and happy? Am I justifying my obsessive behavior by saying I have to make money, support my family, and make a contribution to the world? Is it so that I can avoid seeing who it is that I truly am? Who would I be without any of that? A very peaceful guy. I remember an interview Lama Surya Das had with the Twelfth Gyalwang Drukpa, a little Tibetan guy with a sunhat, big glasses coming down his nose, and a hilarious expression of gleeful laughter on his face. He told Lama Surya Das, “I would say that not doing too much is the important thing. We tend to try to overdo everything. Such conceptual actions just create more karma. Consider nondoing, nonaction for a while, and leaving things as they are.” And here’s the kicker for me. In reference to his own life, the Twelfth Gyalwang Drukpa said, “I have a mission of not doing anything. My goal is not doing anything, ultimately. Just being. That’s it.” Now that’s something worth doing!

Snookered

The waves are breaking gently on shore as I take my regular walk down Baldwin beach on Maui. The drop-dead gorgeous beach stretches a half-mile before me, with hardly a soul on it. I take in the special color of the water today, a light turquoise that extends one hundred yards offshore. My dogs walk along beside me, sniffing for any food that may have been left behind by previous beachgoers. I take a deep lungful of the fresh salt air, clean and pure after blowing across thousands of miles of ocean. A few feet ahead of me I see a dollar bill lying in the sand. How did that get here? I think. I don’t see anyone around. Maybe I should pick it up and find its owner? I reach down to pick it up, but the wind blows it a little further up the beach. Well, maybe it doesn’t belong to anyone any more. Finders keepers. But is it worth chasing a dollar bill? A dollar bill doesn’t get you very far these days. I take a few steps and stretch out my hand to grab it. Once again it flutters in the wind and blows further up the beach. Now this is getting crazy. I’m not going to let that dollar bill get away and disappear into the bushes. The wet bill lies flat on the sand. This should be easy. Grab it quick! I almost have it in my hand when, whoosh, it flutters a few yards away. Damn. I nearly had it. I’ll give it one last try. I take a few steps, pulling the dogs on their leashes. They look up at me, wondering what I’m doing. Now—I’ve got it! I zip my hand out for the final grab, when the bill suddenly takes off high into the air, reeled in by two guys who are laughing hysterically. I start laughing along with them, “I’ve been snookered! Good one!” I yell to them over the wind. “You guys are good!” They’re bent over in laughter and I am too. “Next time put a twenty on!” We’re all in hysterics. I wave and continue down the beach with a big smile on my face. How interesting, I think. Here I was, peacefully enjoying my walk, when out of nowhere, a desire showed up at my feet in the form of a dollar bill. My first reaction was, “Can I return it to its owner?” The next thought was, “I just can’t let this go. I’ve got to grab it.” I jumped, then jumped again, reeled in by my desire, totally forgetting my peaceful walk. Life shows up in wonderful and mysterious ways to show us exactly what we need to learn . . . and I’m still smiling.

Geezer in Paradise

Aging is like going through a funnel. You start out with so much room, spinning so fast, wondering just how far you can go, but in the end you wind up going through the hole. Aging is like going through a funnel. You start out with so much room, spinning so fast, wondering just how far you can go, but in the end you wind up going through the hole.

Albert Brooks There is no set date for it, but geezerdom seems to start around the time when the odometer rolls down towards 70. It’s very different from being a fresh, young “senior citizen” who has just turned 55, and signed up for AARP, excited that you can get discounts at the movies. Geezerdom comes later, when your body starts to fall apart in a major way, your face starts to looks like a cadaver, and you become invisible to the world. I thought that by moving to Hawaii, I could add on a few more years of looking like a young, healthy “senior.” I could at least have a tan, wear my hair in a pony-tail, and look like an eccentric hippie. But not so. The young, hip clerks in grocery stores either look right through me, as if I don’t exist, or they make an effort to be real polite, “Do you need some help with your bags today, sir?” No, of course I don’t need help with my goddamned bags! Perhaps if I lived in Florida, and not Hawaii, it would be different. Both the clerks and the baggers would be older than I am. Well, at least there is one fellow geezer here on the island who hasn’t faded into the woodwork. His name, of course, is Ram Dass, the grand elder statesman who inspired a whole pack of baby boomers through the sixties, seventies, and eighties. He wrote the cult classic Be Here Now way over 35 years ago. His marvelous book Still Here shows boomers how they can age gracefully. Since his stroke ten years ago, after which he was confined to a wheelchair, Ram Dass doesn’t get around much anymore. But he still shows up just about everywhere on Maui to lend his shining presence to events. When he holds his monthly get-togethers, there are always a lot of young people—island hippies, a young mother with a baby at her breast, bronzed young men with sun-bleached hair in a ponytail. Now, unlike me, they don’t see Ram Dass as an old fart. What’s the difference? One difference is that they admire him for all the drugs he has taken (this is Maui, remember?). Another is that he laughs at himself a lot—and at the world. And most of all, he sees no difference between himself and anyone out there. For Ram Dass, there is just life going on around him. He doesn’t judge people their looks, what they’re wearing, or by how young or old they are. And most people don’t judge him; they love him. So the next time I feel invisible or feel judged for being old, it is an opportunity for me to see what is beyond age, beyond looks, and beyond the body. Let’s face it, we scare the hell out of these guys. They’re terrified they will become like us—and they will! If we can find it in ourselves to love them—even if they appear not to see us, or speak slowly and in a loud voice, believing we’re deaf and stupid—love will melt away all the differences. Because love is all there is, and it is who we are.

Arranging the Furniture on the Titanic

You want to hope for something better than what you have right now, don’t you? Otherwise you wouldn’t be hoping. But then, you forget that you have it all right now anyway, and you don’t know it. You want to hope for something better than what you have right now, don’t you? Otherwise you wouldn’t be hoping. But then, you forget that you have it all right now anyway, and you don’t know it. Anthony de Mello I love setting intentions for the New Year. There’s something very satisfying about getting clear on where I’d like to see my life heading. I usually come up with a list of twenty or so intentions, such as “to live simply, laugh often, love deeply” or “to invest wisely, see my assets grow, and have a worry-free income of 5%.” When I look back at the previous year, I’m always amazed to see how many of these intentions have manifested—often in totally unexpected ways. I soon learned how important it is to be very specific in what I ask for. One year I forgot to mention that I wanted a year free from legal hassles. That was the year I got sued. Recently I’ve taken a different approach to setting intentions. I’m more willing to let God, Source, or Spirit be in charge, rather than “me” trying to be in control of my life. I realize that I have no idea how spirit is meant to move through this body-mind. Who is to know if what the “little me” wants is for my highest good? All it wants is to avoid pain and find pleasure. Lately it has come down to one simple intention: to live each moment in present moment awareness—and let God take care of the rest. I've also begun to question whether setting goals really takes us where we want to go in our personal lives. It works well for business, which is quantifiable, but does it work for finding something as abstract as happiness? There are three important things we often miss: 1) All goal setting is future-oriented—and there is no future. It is essentially an attempt to create a new and better dream for ourselves. If we do the steps in our plan, we believe that we’ll feel better, be more fulfilled and happy. But doing things to make the ego feel better is all happening within the dream of illusion. Because it is within the dream, we’ll inevitably experience the pain and suffering that comes along with it, no matter how successful our action plan is. We’ll have a few moments of feeling good, believing that “we” (our egos) have accomplished something. But then dissatisfaction will set in and we’ll go on to the next thing to accomplish, and the next, all towards some impossible end when all our goals are satisfied. But there is no end. Fulfilling our goals can at the most bring short-term happiness (otherwise, why would we need to go on to the next one?). We have to ask what it is that we really want, beyond satisfying our desires. What if we were to turn our attention inward to finding happiness that doesn’t come and go, and fulfillment where there is nothing that needs to be filled? The first step is going beyond the illusion that there is something out there in the future that will make us happy. As Eckhart Tolle says, “The joy of Being, which is the only true happiness, cannot come to you through any form, possession, achievement, person, or event—through anything that happens. That joy cannot come to you—ever. It emanates from the formless dimension within you, from consciousness itself and thus is one with who you are.” 2) Most intention setting is based on the fundamental assumption that there is something wrong with me, and I have to somehow “fix” it. For whatever reasons, I am not enough just the way I am—because if I was enough, what would there be to “fix”? Working with intentions distracts us from the realization that we already are whole and complete. Can you conceive of the radical thought that right in this moment there is absolutely nothing missing in your life? The mind will immediately say, “No, no that’s not possible! I need to be a better husband, I need to be more surrendered, I need to inspire others.” But what if there was absolutely nothing missing in your life right now? Where would that leave you? You’d have to let go of all your dreams about the future and realize that right now is all there is. As Alan Cohen says, “You are not a black hole that needs to be filled; you are a light that needs to be shined. The days of self-improvement are gone, and the era of self-affirmation is upon us. It is time to quit improving yourself and start living.” 3) No matter how many action steps you take, no matter how many goals you set, how many values you identify, you’re still trying to patch up the ego—and the ego, by its very nature, is unfixable. It’s the job of the ego to be dissatisfied and always want more. Trying to fix the ego is like trying to plug the holes in a sinking ship. The boat is eventually going to sink. The question is—are you willing to jump off the boat and be free? If you were “enough,” if you had no fear, and you were living in the fullness of who you are, would you need an action plan? Does someone like Eckhart Tolle live his life from an action plan? I doubt it. From that place of being fully present, you would know that in every moment you were doing exactly what you needed to be doing, that your life was being revealed in exquisite perfection from moment to moment. What if your 2009 action plan was not to have a plan—other than to offer love now—and trust that your life is unfolding perfectly just as it is? David Deida speaks to this when he says, “Enlightenment is the capacity to open and be lived by the love that is already, miraculously, living your life, despite all your current torment and refusal. Instant enlightenment is to offer love now—whatever the circumstance—without waiting for things to get better.” Setting goals can be helpful in this difficult world, even if it is rearranging the furniture on the deck of the Titanic as it sinks slowly into the silent sea. We might as well enjoy the ride. Action plans, workshops and self-help books help us to feel good about ourselves. But they will never bring us the happiness we are looking for. That’s because we are creating our goals using the conditioned mind—the mind that feels it needs to find solutions and come up with strategies to solve its problems. It asks all the wrong questions, based on likes and dislikes, the past and the future, and avoidance of pain. To go beyond conditioned mind to clear mind, it helps to enter into a process of self inquiry, asking the question, “Who is it that wants to make goals?” or “What is it that needs to be renewed”? Until we are willing to drop into that place of “not-knowing” that these questions lead to, achieving every goal on our list will not bring us inner peace. That can only come through unconditional awareness, where we don’t need anything and there’s nowhere further to go. That doesn’t mean we don’t do anything with our lives, it just means that there is no longer anyone there “doing” it. Having said all this, I'm still having fun setting intentions for the New Year—though I'm less attached to the results.

When Bodies Break Down

To identify oneself with the body and yet to seek happiness is like attempting to cross a river on the back of an alligator. To identify oneself with the body and yet to seek happiness is like attempting to cross a river on the back of an alligator. Ramana Maharshi After a week-long trip to Washington, DC, I come back to Hawaii with a cold, a nagging cough, and a body that feels like it’s been run over by a truck. My eyes are burning, my brain is in a fog, and all I want to do is climb into bed and sleep. When I finally do sleep, I wake up just as tired as before. This fatigue is nothing new. Recently I found out that I have parasites, and may have been carrying them for twenty years. I did one of those unpleasant treatments, which is worse than the disease. Just yesterday I found out that the treatment didn’t work, and not only that, the parasites are even more active! No wonder I’m so tired all the time. Together with a minor squamous cell surgery that is not healing, and the continuing existence of prostate cancer cells in my body, I feel like one of those old rust-bucket cars, where the muffler falls off, and as soon as you fix that, then the transmission goes. One of the side effects of getting older is that the body seems to break down with alarming frequency. I love what Robert Adams, a spiritual teacher, said. This was when he was ill with Parkinson’s disease, and shortly before his death in 2004: “I want to let you in on a little secret. There are no problems. There never were any problems, there are no problems today, and there never will be any problems. Problems just mean the world isn’t turning out the way you want it to.” The challenge, as always, is how to be OK when things are not going the way you’d like them to. What can we do? 1. Accept that this is what is happening. We’ll find ourselves a lot more peaceful if we can say, “OK, this is what is happening. If I fight it or struggle against it, it will only create more suffering. 2. We can also say, “I have a preference that things would be different, but this is what is. Right here, right now, in this moment, all is well. Behind my discomfort there is a peace that is unchanging. If I can be still for an instant, it is there.” 3. We can take whatever steps are necessary to take care of things. I can see my doctor about another way of getting rid of the parasites; I can work more on an anti-cancer diet; I can be grateful for the love that is present in my life in every moment.

|

-718582.jpeg) Last night I watched a captivating1958 film called Inn of the Sixth Happiness, based on the true story of a British maid named Gladys Aylward (played by Ingrid Bergman), who leads fifty children over the mountains to safety in China after the Japanese invaded in 1937.

Last night I watched a captivating1958 film called Inn of the Sixth Happiness, based on the true story of a British maid named Gladys Aylward (played by Ingrid Bergman), who leads fifty children over the mountains to safety in China after the Japanese invaded in 1937.