Tectonic Shift

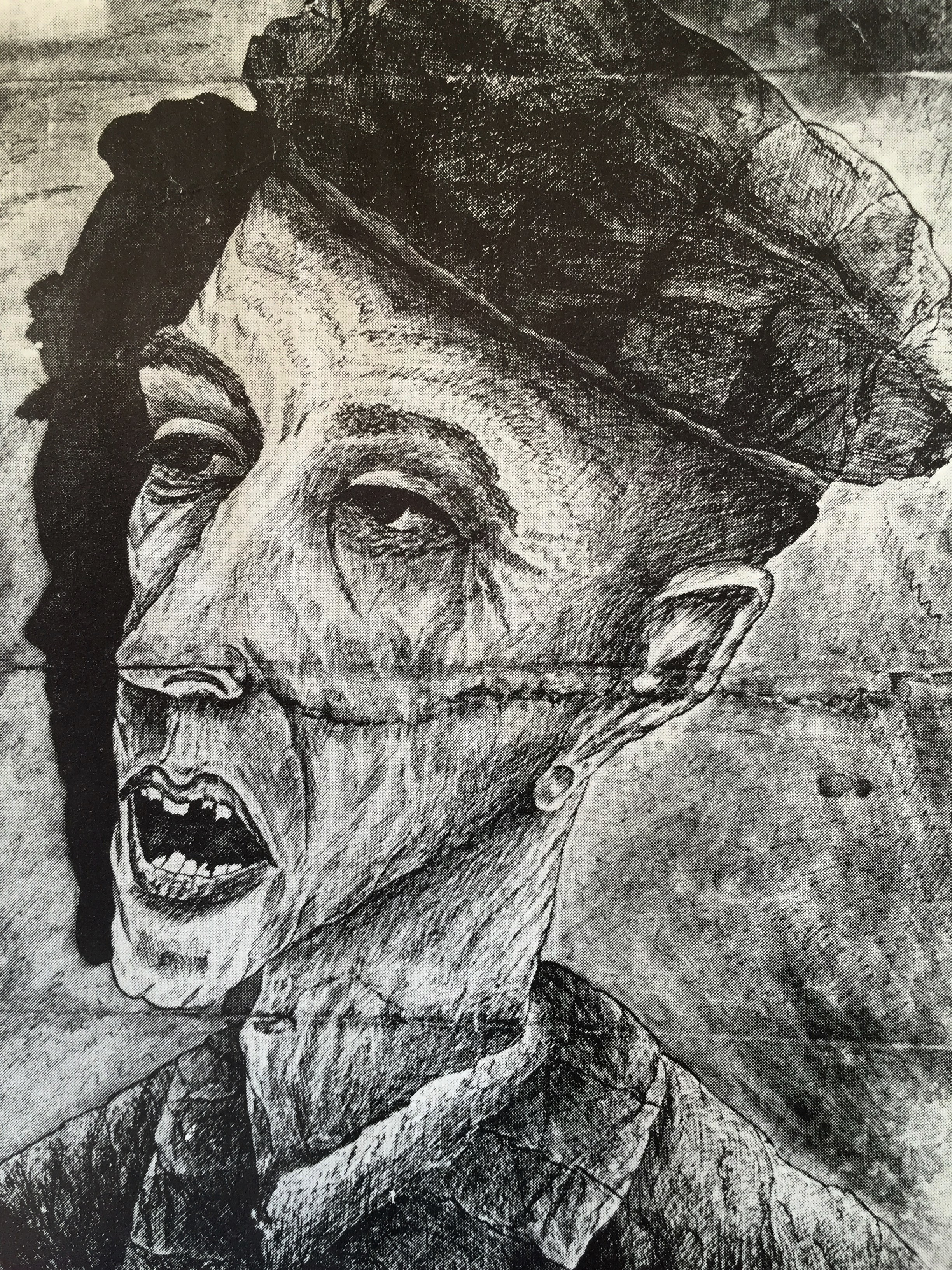

When I was in my early thirties and a cocky young art history professor living in Toronto, Canada, the editor of artscanada asked me to write a feature article on Gershon Iskowitz, one of Canada’s foremost painters. I knew something of his story. Gershon was eighteen when the Germans invaded Poland in 1939. He and his family were separated and he spent three years in forced labor camps, where he tried to escape several times. In 1942 he was sent to the infamous Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz. Eighteen months later he was transferred to Buchenwald. Just before the Americans liberated the camps, he was shot in the hip while trying to escape and left for dead. Somehow he survived.

After a long recovery, he emigrated to Canada in 1949. When I met him in the early seventies, he had just turned fifty and was coming into prominence as an artist. I was a little intimidated about meeting a concentration camp survivor, but to my delight, we soon became best of friends.

Several times a week, I’d visit him in his studio on Spadina Avenue in downtown Toronto. His studio was up three long, grimy flights of narrow stairs lit by a bare bulb overhead. I’d knock on his metal door, and would hear him ask, “Who is it?”

“It’s me, Peter,” I’d say. Then I’d hear thump, thump, thump as he limped across the wooden floor. One of his shoes was built up 2 inches to compensate for his shorter leg.

Gershon opened the door, greeting me with a broad grin. He had full lips, a prominent nose, and playful brown eyes. Nothing in his face revealed the suffering of his past. As always, he was neatly dressed in grey flannels and a blue V-neck sweater. “Peter, how are you? Good to see you!” he’d say, giving me a hug. I always liked to feel his barrel chest against mine; it reminded me of my dad’s.

“I’m good, I’m good,” I’d reply.

“How about a little vodka?” he’d ask. He’d pronounce the “v” as a “w.”

“Sure, sure.”

Always the same routine. Off he’d go to his fridge and grab a bottle of Stolichnaya from the freezer and two shot glasses.

We’d sit down and talk about our lives, sipping on the cold vodka. It wasn’t long before I had a good buzz going. “How are all your girlfriends?” I’d inquire with a wink. He’d give a low-bellied chuckle. “Fine, fine!” Gershon had an adoring group of young women that he liked to flirt with. It never went further than that, but I often kidded him about getting hooked up.

As we’d talk, my eyes couldn’t help but wander over to his forearm, where the tattooed numbers from the camps were clearly visible. Every so often we’d talk about his time in the camps, and his early family life in Kielce, Poland. None of his family survived the war. There was never any self-pity when he told me these stories. He seemed almost embarrassed to tell me. In the camps, he would find ways to get drawing materials from the guards, and sketch other prisoners. He knew that if he were caught, he would be shot. I asked him why he did it. “Why did I do it? I think it kept me alive. There was nothing to do. I had to do something in order to forget the hunger. It’s very hard to explain, but in the camp painting was a necessity for survival.”

After talking for a while, Gershon would show me his current paintings, which are lined up along the walls of his long studio. They are huge, colorful, semi abstract paintings, as if looking down at the world from above. “They’re real,” he would say. “I see those things.” The year is 1971, and he’s just been invited to represent Canada in the Venice Biennale; I’ve agreed to make a documentary film on him. “All my life I’ve been searching,” he tells me. “I don’t give a damn about society. I just want to do my own work – to express my own feelings, my own way of thinking.”

Gershon’s life fascinates me. Day after day he has the same routine. He gets up at noon, goes out for some breakfast, then sees friends or buys art supplies. In the evening he goes to Grossman’s, the local tavern next door, and has a few beers. Around 10:00 he starts painting, working through the night until 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning. Night after night he does his solitary work, sometimes applying up to 30 layers of paint to get the effect he wants. For years he received no recognition, living a solitary life. I’d often ask him, “Gershon, how do you do this? Don’t you get lonely?” He’d laugh, looking into some far off place. “No, no. I’m alone, but I’m not alone.”

Gershon died in 1988. I’ve thought of him often over the intervening years. His one-pointed creative focus has always been an inspiration for my writing. His ability to find happiness in the face of unimaginable horror has also inspired me. He’s especially in my thoughts now that I’ve started spending time living on my own. I’d spent fifty years of my life in very intense full-on relationships. I’d seen two wives die, and recently became divorced after a third marriage. Even though I’m still close friends with my former spouse, it was a huge adjustment not to have someone to share every moment of my life with. I quickly realized that being in relationship was a convenient way of avoiding being alone.

Now I have a brand new opportunity to face what I’ve avoided all my life. A part of me is thrilled at the challenge. For the first time ever – and I mean ever – I’m able to do what I want to do, when I want to do it. The freedom is exhilarating.

But then there are those moments when 8:00 pm comes along, and I’ve finished my day, had my glass of wine, eaten dinner alone, had another glass of wine, and gotten bored with television. What do I do now? Read a book? Phone someone? Take some Ambien and knock myself out? How do people do this? I try to pump myself up, saying how good it feels to be on my own. Ok, I think, I can live like a monk for a while. I can do this. And then, mercifully, I feel it’s late enough to go to bed. Sleep comes, and I have to deal with getting up every hour or two to pee, stumbling around in the dark. The house feels very empty. “What if I get sick?” “What if . . .?” my mind goes on, making it difficult to get back to sleep. Dawn comes. Another day.

I think of all the people I know who are single and living alone. Some do better than others. Women seem to do better than men. I’m appalled by how some of my friends create tiny cocoons, protecting themselves from any intrusion. Their world is neat and ordered, devoid of any emotional juice. Oh shit, I don’t want to become like that. Yet, I notice, to my dismay that I’m becoming obsessive about having my counters spotless, my remotes carefully lined up on the table, my bed made up every morning. And yes, talking to myself out loud. And dancing alone around my living room with tears streaming down my eyes as Andrea Bocelli and Sarah Brightman sing Time to Say Goodbye.

I think of all the people I know who are single and living alone. Some do better than others. Women seem to do better than men. I’m appalled by how some of my friends create tiny cocoons, protecting themselves from any intrusion. Their world is neat and ordered, devoid of any emotional juice. Oh shit, I don’t want to become like that. Yet, I notice, to my dismay that I’m becoming obsessive about having my counters spotless, my remotes carefully lined up on the table, my bed made up every morning. And yes, talking to myself out loud. And dancing alone around my living room with tears streaming down my eyes as Andrea Bocelli and Sarah Brightman sing Time to Say Goodbye.

For months I wrestle with my fears. I watch films like Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun, where a young 13-year-old boy (played by Christian Bale) is abandoned by his parents at the beginning of World War II and has to survive using his wits. I spend session after session working out my abandonment issues with my two therapists, David and Tom. These fears go back to when my mother died when I was 12, and I spiraled into depression and loneliness.

For months I wrestle with my fears. I watch films like Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun, where a young 13-year-old boy (played by Christian Bale) is abandoned by his parents at the beginning of World War II and has to survive using his wits. I spend session after session working out my abandonment issues with my two therapists, David and Tom. These fears go back to when my mother died when I was 12, and I spiraled into depression and loneliness.

Then, something begins to happen. I begin to feel a tectonic shift, as if some, great, overwhelming, enormous, solid mass is slowly beginning to move. Instead of being in a panic at being alone, I begin to crave it. Instead of filling up my empty time with seeing friends, I celebrate having time to myself. Instead of escaping into my work, I am fully present. After years of emotional spinning, it feels like I’m discovering my own inner compass.

In the evening I sit alone on my lanai before dinner, enjoying the extraordinary view up to the top of Mt. Haleakala, lit by the later afternoon sun. I hear the roar of the stream in the gulch after a big rainfall and the sound of birds singing as they find their nests for the night. I smell the incense I’ve lit as it wafts through the door to where I’m sitting. Things don’t get much better than this, I think. I am at peace.

In the evening I sit alone on my lanai before dinner, enjoying the extraordinary view up to the top of Mt. Haleakala, lit by the later afternoon sun. I hear the roar of the stream in the gulch after a big rainfall and the sound of birds singing as they find their nests for the night. I smell the incense I’ve lit as it wafts through the door to where I’m sitting. Things don’t get much better than this, I think. I am at peace.

In these moments my mind goes back to those precious times with Gershon so many years ago. His voice comes alive inside me, as I ask him. “Gershon, isn’t it hard to be alone?” “No,” he smiles mysteriously. “I’m alone, but not alone.” He knew. He knew.